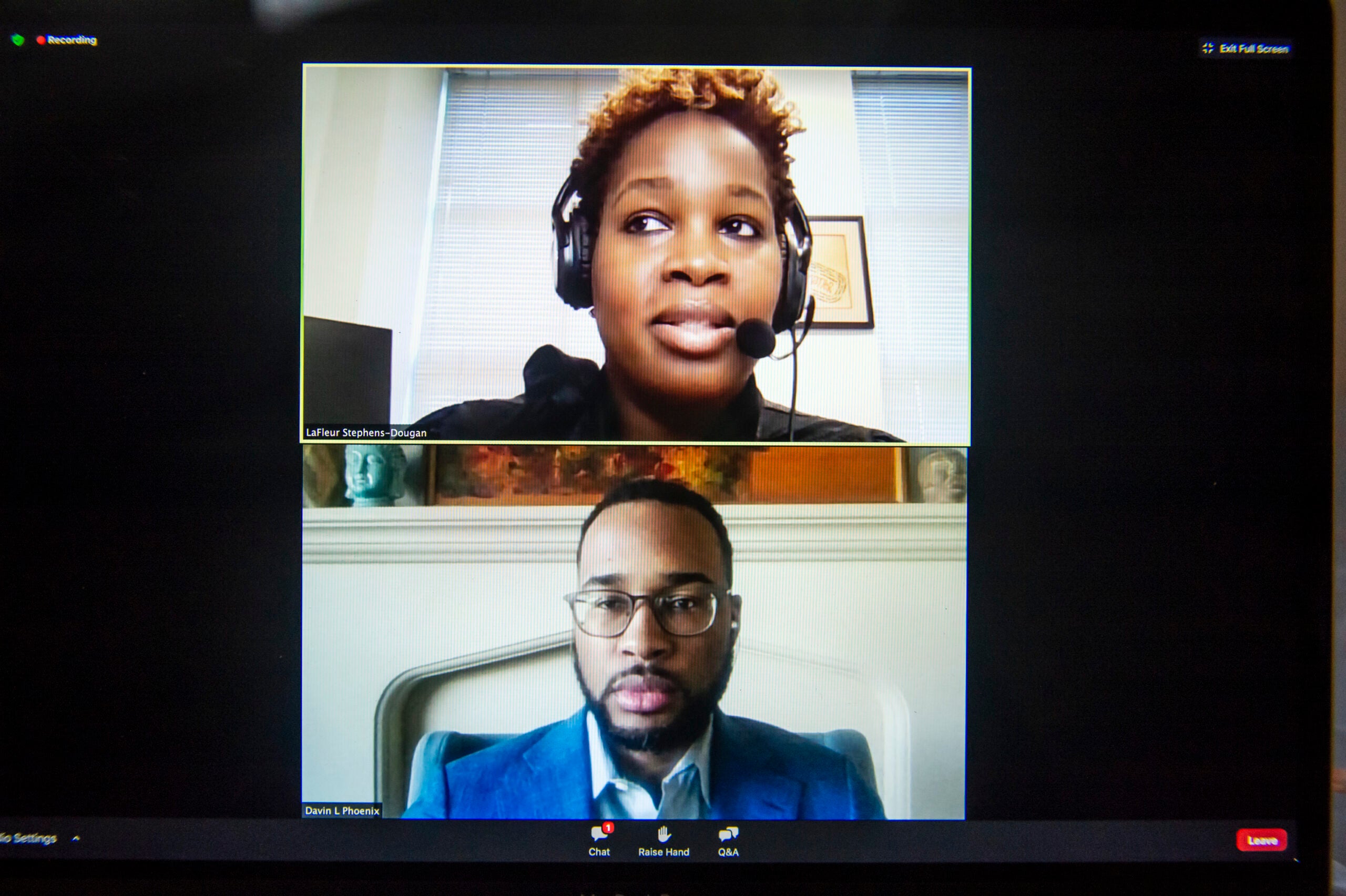

LaFleur Stephens-Dougan (top) researches the subtle ways that racial appeals come into political speech. She spoke with Davin L. Phoenix (bottom) on Monday.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

How politicians practice ‘racial distancing’ with communities of color

They tailor speech to be supportive without alienating white voters, professor says

Many politicians find themselves walking a fine line when it comes to talking about the African American community, LaFleur Stephens-Dougan, Princeton University assistant professor of politics, says. They want to simultaneously voice their support for policies, positions, and attitudes widely held by African American voters without alienating white supporters, a rhetorical strategy she refers to as “racial distancing.”

Stephens-Dougan, a former Sheila Biddle Ford Foundation Fellow at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, researches the subtle, often surprising ways that racial appeals come into political speech. She shared those insights in a Monday talk sponsored by the Hutchins Center. The talk shared its title with her recent book, “Race to the Bottom: How Racial Appeals Work in American Politics.”

Moderated by Davin L. Phoenix, assistant professor of political science at the University of California-Irvine, her talk gave a perspective that went beyond the Trump era. She noted that President Trump has made plenty of racial appeals in his own speeches, both explicitly (denouncing Mexican immigrants as rapists in his 2016 campaign) and implicitly (warning suburban housewives this year that “low-income housing” would invade their neighborhoods). Yet, she said, “The landscape is even wider in terms of who uses racial appeals, and why they are effective.”

And she noted that such appeals have been used in the past by Republicans and Democrats alike.

Reading from her book, Stephens-Dougan referred to a pivotal moment in recent racial history: the west Baltimore protests that broke out in 2015 when a Black man, Freddie Gray, was fatally injured while in police custody. The ensuing riots, she said, “placed a national spotlight on race, justice, police brutality, and the distrust between African American communities and their local government. The nation was looking to the first Black president to address the racial tension. How would [President Obama] respond?”

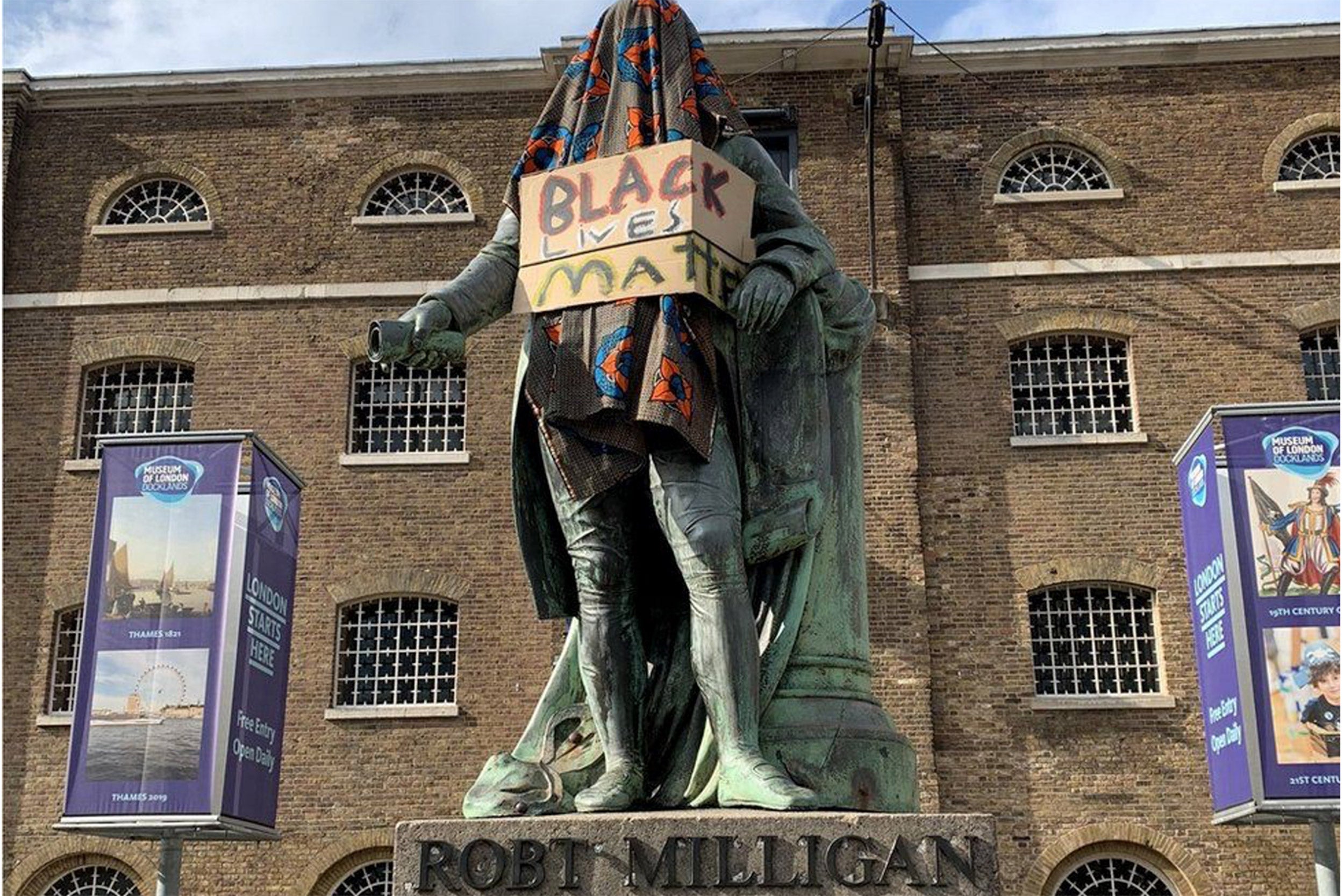

LaFleur Stephens-Dougan said that African American politicians, like the one pictured here with the Confederate flag, are not immune from the pressures of appeasing their constituents.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The answer was that Obama’s responses tended to be extremely tempered: He denounced racism while also sympathizing with police and assailing acts by protesters that seemed violent or destructive. “The resulting fallout was usually that Obama was criticized in conservative circles for being anti-police, while he was criticized in liberal circles for being far too silent on an issue that disproportionately affected African Americans.” Obama would eventually denounce rioters as “criminals and thugs” who damaged their own communities.

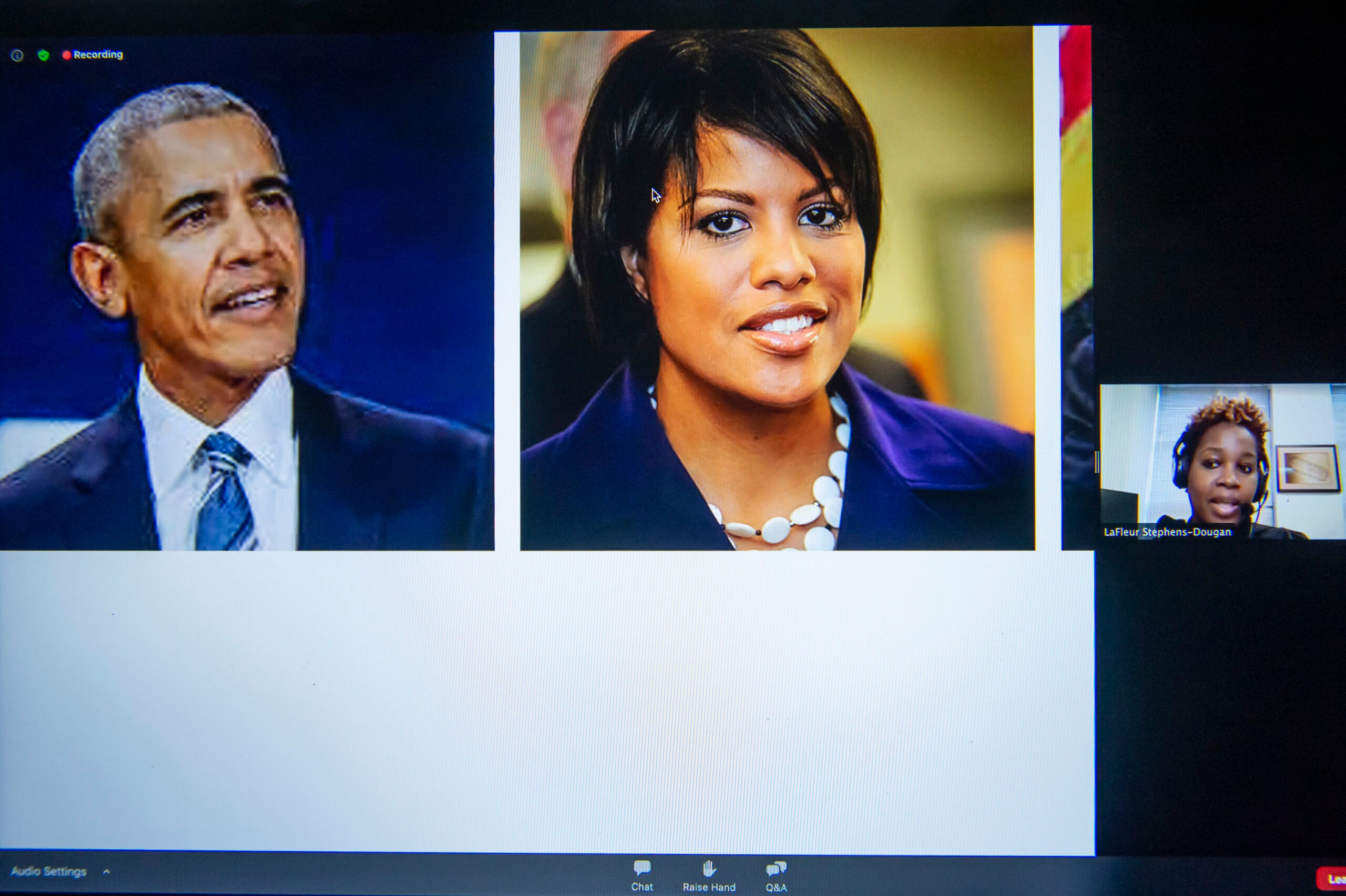

This marked a major shift in Obama’s rhetoric, Stephens-Dougan said: His use of the racially-charged word “thugs” was shared by the city’s Democratic, African American mayor, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake (who later walked it back), and by the state’s white Republican governor, Larry Hogan.

“All three politicians were united in their use of racially inflammatory language despite the diversity of their racial and political backgrounds,” she said. And she noted that all three were criticized for it — notably by Baltimore City Councilor Carl Stokes, who said that “thug” was “a euphemism for the N-word.”

In 2015, President Obama and Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake used the racially-charged word “thugs” when describing the protesters in the Baltimore riots.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Yet, she said, use of the word served a purpose for both sides: “Hogan was reinforcing his party’s reputation for being tough on crime, while Obama and Rawlings-Blake were distancing themselves from their party’s reputation for being soft on crime.” Just as importantly, the latter two were also eschewing any racial allegiance with the mostly Black protesters. This, she said, was an example of “racial distancing,” which she characterized as “the phenomenon whereby politicians convey to racially moderate and to racially conservative whites that they will not disrupt the racial status quo.”

In majority white jurisdictions, she said, political candidates have an incentive to show that they will not “cater to Black interests,” but they must also show that they are not racially insensitive. As a result, she said, Democratic and African American politicians are increasingly talking about race in a manner that distances them from a racially liberal agenda.

This sort of “racial distancing” is meant to challenge the stereotype that these politicians are beholden to a particular minority. This played out most recently in the last election, when Democrats balanced their outreach to communities of color with “trying to get that elusive white American swing voter who might have switched from Obama to Trump in 2016.” One example would be the use of coded racial terms, like “urban” or “inner-city,” over explicit ones.

Responding to one of Phoenix‘s questions, Stephens-Dougan noted that the racial unrest of the past summer may mark a turning point away from softer, racially distanced messages. “I’d argue that this year that we’ve seen a racial reckoning that’s made it more difficult for Democratic candidates in particular to engage in racial distancing. There is a groundswell among young people against anything that is seen as perpetrating racism. So Democrats are more constrained in some ways. We see this borne out in the Joe Biden campaign, where there was a lot of push for him to have an African American running mate, even if that might be largely symbolic.” Still, she said, Biden has had to maintain a balance — “admitting that systemic racism is a thing, while being clear that he is not especially liberal.”

An audience member asked what she made of Trump’s apparently increased appeal to Black and Hispanic men in the past election. She responded that sexism may be part of the answer: “The type of messaging that Trump has engaged in might appeal to a non-trivial fraction of men of color in terms of this idea of protecting womanhood and the other gendered tropes that he has engaged in.” At the same time, she said, Trump at least made his racial messages more implicit. “We know what he’s talking about what he says ‘suburban housewives’ and ‘low-income voters,’ but at least he didn’t come out and say it.”